[bl]R[/bl]esearch has been integral to Foundations of Science Literacy (FSL) since its inception, both to inform its development and to provide empirical evidence of its efficacy in promoting high quality, early science learning.

Empirical Evidence

In a randomized control trial, we investigated the impact of FSL on classrooms, teachers, and children. Classrooms were randomly assigned participate in FSL during a school year (FSL group) or to continue with “business as usual” (Control group). To evaluate the impact of participation in FSL, both FSL and Control classrooms were assessed in multiple ways during the fall (pre-FSL implementation) and the spring of the school year (post-FSL implementation).

Effects on Teachers

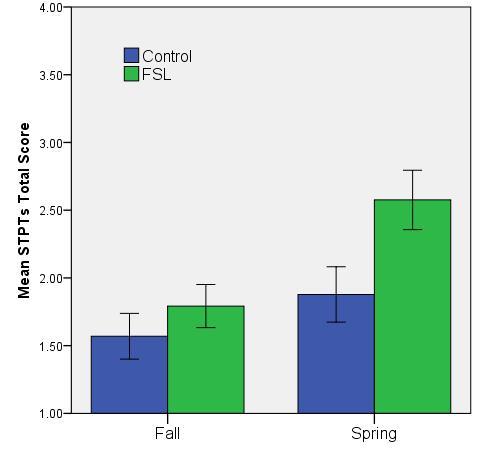

Results indicated that FSL improved teachers’ knowledge of effective science teaching practices.

[frame_left][lightbox href=”http://foundationsofscienceliteracy.edc.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Research_EffectTeachers.jpg” desc=”Mean STPTs Total Score – Control vs FSL”] [/lightbox][/frame_left]Teachers completed Teacher Performance Tasks (TPTs), assessing their understanding of how young children learn science and their ability to apply that knowledge in common teaching scenarios. Controlling for fall scores, FSL teachers had significantly higher spring scores compared to Control teachers.

[/lightbox][/frame_left]Teachers completed Teacher Performance Tasks (TPTs), assessing their understanding of how young children learn science and their ability to apply that knowledge in common teaching scenarios. Controlling for fall scores, FSL teachers had significantly higher spring scores compared to Control teachers.

Effects on Classrooms

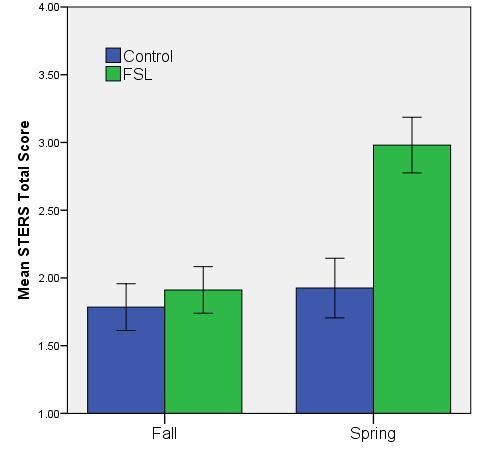

Results indicated that FSL improved the quality of science instruction and the science learning environment.

[frame_left][lightbox href=”http://foundationsofscienceliteracy.edc.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Research_effectclassrooms.jpg” desc=”Mean STERS Total Score – Control vs FSL”] [/lightbox][/frame_left]Classrooms were observed using the Science Teaching and Environment Rating Scale (STERS), assessing the ways that teachers foster a classroom environment and provide instruction that promotes hands-on, collaborative science learning, conceptual understanding and language development. Controlling for fall scores, FSL classrooms had significantly higher spring scores compared to Control classrooms.

[/lightbox][/frame_left]Classrooms were observed using the Science Teaching and Environment Rating Scale (STERS), assessing the ways that teachers foster a classroom environment and provide instruction that promotes hands-on, collaborative science learning, conceptual understanding and language development. Controlling for fall scores, FSL classrooms had significantly higher spring scores compared to Control classrooms.

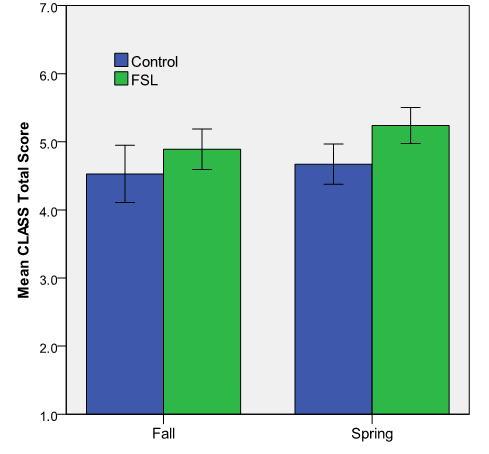

Results indicated that FSL improved general classroom quality.

[frame_left][lightbox href=”http://foundationsofscienceliteracy.edc.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Research_effectclassrooms2.jpg” desc=”Mean CLASS Total Score – Control vs FSL”] [/lightbox][/frame_left]Classrooms were observed using the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS1), assessing overall quality of teacher-child interactions. Controlling for fall scores, FSL classrooms had significantly higher spring scores compared to Control classrooms.

[/lightbox][/frame_left]Classrooms were observed using the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS1), assessing overall quality of teacher-child interactions. Controlling for fall scores, FSL classrooms had significantly higher spring scores compared to Control classrooms.

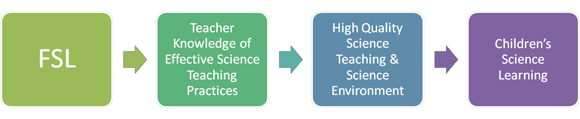

Cascading Positive Effects

Based on these positive effects on teacher’s knowledge and, in turn, on their science teaching practices, it was expected that FSL would ultimately lead to greater science learning for children.

[frame] [/frame]

[/frame]

Effects on Child Learning

As predicted, results indicated that FSL improved children’s understanding of science concepts and their ability to think scientifically.

[frame_left] [/frame_left]Children were assessed using the Preschool Assessment of Science (PAS), a set of hands-on tasks designed to capture young children’s understanding of physical science concepts and science process skills. Controlling for fall scores, children in FSL classrooms were significantly more likely than children in Control classrooms to “think like scientists” by making accurate observations and predictions about physical phenomena, and by being able to flexibly shift their thinking based on new evidence.

[/frame_left]Children were assessed using the Preschool Assessment of Science (PAS), a set of hands-on tasks designed to capture young children’s understanding of physical science concepts and science process skills. Controlling for fall scores, children in FSL classrooms were significantly more likely than children in Control classrooms to “think like scientists” by making accurate observations and predictions about physical phenomena, and by being able to flexibly shift their thinking based on new evidence.

1 Pianta, R. C., LaParo, K. M., & Hamre, B. K. (2008). Classroom Assessment Scoring System&trade (CLASS™) Manual, Pre-K. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.